#brackish ecosystems of the american atlantic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Spartina Alterniflora (aka Sporobolus Alterniflorus) - Smooth Cordgrass

Smooth Cordgrass is many things: a signifier of salinity, an extremophile, a creator of habitat, and a peat builder. This lovely species typically colonizes the low marshes of heavily salinited areas near the ocean where other plants cannot. It is endemic to the Atlantic coast of both North and South America, forming the backbone of most brackish ecosystems. While it may appear to create a monoculture within its habitat niche, Cordgrass actually does such an important job in building marsh.

As sediments collect from rising tides the colonal roots of this plant trap nutrients to accure peat and in turn provides a lot of habitat for mussels, fiddlercrabs, nesting birds, and other prey species. The process of building this peat is called marsh accretion, its what allows marshes to build elevation and migrate in the face of sea level rise. Similar to Mangroves, Cordgrass can monopolize saline habitats due to its ability to survive tidal conditions and secret salt from its leaves (zoom in on the leaf with my finger to see salt crystals collecting).

Salt grass can grow up to six feet tall and typically spreads colonally or via seed. As sea levels rise many existing salt marshes are dying, however, cordgrass individually is rather resilient, as it is one of the few species which can cope under increasing exposure to salinity. In Philadelphia we see this species slowly creep up the waterways as salinity increases up the Delaware River. Spartina Alterniflora is very famously invasive in other areas of the world however here where there is biological control we see heavy losses to existing ecosystems (especially in the Chesapeake bay) as stresses from climate catastrophe increase.

I have a lot of love for this species and it's ability to carve out a bountiful ecosystem in what is considered a desert to almost all other lifeforms (image above: Nest made from cordgrass).

#native plants#brackish ecosystem#Delaware bay#spartina alterniflora#smooth cordgrass#salt marsh#brackish ecosystems of the american atlantic#i believe spartina is an extremely distinct genus which is why i don't use sporobus personally#but that's a very Mid-Atlantic opinion apparently#which the science is still debating a bit on#plant profiles

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The magic of mountains in Mesoamerica.

Active volcanoes covered in thick green coats of misty cloud forest and rainforest. A focal point, an epicenter, the meeting place between two oceans and two continents. The origin of the revered orchid, vanilla!

Here, an absurd amount of endemic species with very small limited distribution ranges in Central America and Mesoamerica. Out of about 700 species of reptiles living in Mesoamerica, over 200 live nowhere else. Out of about 550 species of amphibians living in Mesoamerica, over 350 live nowhere else.

And this extreme biodiversity is boosted by the presence of so many mountain ranges located within the tropics, so that “cooler” habitats (at high elevations) can exist closer to the heat of the equator. And orographic uplift (rain in the mountains) means that humid and wetter habitats (”sky islands”) can exist closer to dryland habitats (arid valleys). And also different habitats can occur so close next to each other along the slopes of a single mountain (”altitudinal zonation”). And this is in addition to how the region is the meeting place between ecosystems of South America and North America, and between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean.

So that there can be about 30 species of hummingbirds that only live in Mexico and Central America.

Or there can be like 11 different species of venomous palm pit vipers all in the same genus living in just a couple of mountain ranges between merely San Jose and Ciudad de Guatemala.

Or how, within the borders of Guatemala alone there are at least 40 different species of salamanders, and most of them are so-called arboreal “climbing salamanders” which live in bromeliads and fern mats growing in the branches of trees.

Like how the mangrove hummingbird only lives in brackish swamps of the mangrove forests along the seashore of a stretch of coastline only within the borders of Costa Rica, and the hummingbird depends on the nectar from the flower of one species of tea mangrove (Pelliciera rhizophorae).

Consider the Motagua beaded lizard (Heloderma charlesbogerti), a species of venomous lizard in the same genus as and closely related to the beloved Gila monster. It’s an endemic species, living only in one valley, and there are less than 200 Motagua beaded lizards surviving in the wild. It’s “one of the rarest and most endangered lizards on the planet.” And for food, it relies on the eggs of the Motagua spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura palearis), of which there are less than 2,500 surviving in the wild, making it another of the planet’s most endangered lizards. Two lizards, found nowhere else, entwined in a relationship, almost extinct. But it gets more incredible. For food, the Motagua spiny-tailed iguana itself relies on the fruit of several cactus species. (One of the dryland plants that the iguana relies on is Pereskia lychnidiflora, one of the only cactus-type plants that basically produces leaves.) Without the cactus fruit, the Motagua spiny-tailed iguana would disappear. Without the Motagua spiny-tailed iguana’s eggs, the venomous Motagua beaded lizard would disappear.

Think of frogs like Bromeliohyla bromeliacia. There are colorful poisonous tree frogs whose aquatic baby tadpoles swim around in the tiny pools of rain water that temporarily collect in flowers growing on tree branches and in forest canopies. A whole multiplicity of “small” worlds existing, some ephemerally and some more permanently. Whole unique ecosystems in the treetops.

Here, the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean nearly kiss. They are separated by less than 70 kilometers of land! You could stand on the peak of a Central American volcano, drinking native cocoa flavored with vanilla, and nearly toss a stone between these two marine universes.

Amphibians, reptiles, and hummingbirds in Mesoamerica were just like: “Let’s find a mist-shrouded cloud forest near the slopes of an active volcano in a single mountain range and only live in an area under 5 square kilometeres in size and only between the elevations of 1450 and 1650 meters.” (This is the famous recently-extinct golden toad of the Monteverde cloud forest and the slopes of the Arenal volcano.) Then these creatures were like: “Also I’m probably extravagantly colored with neon blue or fiery orange or bright pink or something.”

“And I’ll live nowhere else on the planet.”

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Forests Need Salmon

(Originally posted at my blog at https://rebeccalexa.com/why-forests-need-salmon/)

One of my favorite fall activities is to check local streams for salmon runs. Here in the Pacific Northwest, and extending north into Alaska, we have seven species of anadromous Salmonidae: chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), coastal cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii), and steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss). My favorite run is the chum salmon that run up Ellsworth Creek in southwest Washington each fall, but I’m honestly just happy to see any migrating salmon. And as I hike through stands of ancient western red cedar (Thuja plicata), I like to think about the many ways in which these and other forests need salmon for their ongoing health.

Anadromous fish are those that are born in fresh water, spend much of their adult lives in salt water, and then return to fresh water to spawn. Some, like Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and some populations of American shad (Alosa sapidissima) are iteroparous, meaning they can make this journey multiple times in a lifetime. Pacific salmonids, on the other hand, are semelparous, meaning that they spawn once and then die shortly thereafter. (From here on out I am going to use “salmon” as a general, casual term referring to both the Oncorhynchus species, and the steelhead and cutthroat trout.)

Pacific salmon were originally freshwater fish that inhabited lakes and slow-moving rivers. Somewhere around 25 million years ago, the climate cooled significantly, with average temperatures dropping almost twenty degrees F. We’re not sure at what point after this the salmon began expanding into brackish estuaries and then the Pacific Ocean itself, but when they did they found rich sources of food unlike what they had access to in fresh water. Over time, they evolved a life cycle that let them be born in the relatively safe shelter of freshwater streams, and then go out to the ocean to feast on the banquet found there when they were large enough to have a better chance of survival.

Eventually salmon runs could be found in streams as far inland as eastern Idaho, eastern British Columbia, and the southern two-thirds of Alaska (with some Alaskan runs even crossing over into Canada!) And until the arrival of European colonizers, these streams consistently provided indigenous people all along the Pacific coastline an incredibly important source of food, cultural and economic trade, mythos, and more. Unfortunately, the newcomers overharvested the salmon, dammed and destroyed streams and other habitat, and of course spearheaded the causes of anthropogenic climate change.

Indigenous people fish for salmon at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River. As the single longest continuously inhabited community in North America (over 15,000 years!), this location was a home and hub of cultural activity for many indigenous tribes and communities across the region before it was flooded by the completion of the Dalles Dam in 1957.

All these factors have led to a precipitous decline in the size of both salmon runs, and the salmon themselves. This isn’t just detrimental to indigenous communities, though. It also threatens the health of forests all throughout the salmons’ range.

A forest isn’t just made of trees. It’s composed of entire plant communities, fungi (including mycorrhizal species), and the animals, bacteria, and other living beings that share space with them. When salmon travel up and down the waterways as fry, and then later to spawn as adults, they have a direct impact on that ecosystem.

Salmon fry are an important source of food for larger fish, amphibians, birds, and other beings that seek food in the water. In fact, part of why salmon lay so many eggs (over 5,000 in the case of chinook!) is because most of the fry that hatch will never make it to adulthood. But adult salmon aren’t safe from predation on their return trip to their birthplaces. In fact, they are caught and eaten by a wide variety of animals from bears to eagles, wolves to osprey, sea lions to bobcats.

Bears are of particular interest here. Brown bears (Ursus arctos) are well-known for gorging on summer and fall salmon runs to build up massive amounts of fat in preparation for winter hibernation. (Katmai National Park even celebrates their bears during Fat Bear Week every October!) You can watch video feeds of several bears hanging out in their favorite fishing spots by waterfalls and in the flow of the river.

Imagine that you are a young bear, perhaps recently forced to independence by your mother who is now focused on your younger siblings. You have to not only start catching fish without her protection from bigger bears, but you also need to make sure those stronger bears don’t steal your catch. What’s the best thing to do? Run far away into the woods to eat your salmon in peace, then leave the remains among the trees and head back for more.

If the fishing is good, bears will often eat only the fattiest parts of the salmon like the brains and skin, and then leave the rest behind for scavengers. The nutrients in the salmon then disseminate throughout the forest, whether carried in the digestive systems of animals, or broken down in place by decomposers. This helps make the nutrients available to the plants, particularly trees which may store massive amounts of nutrients in their trunks; when the trees die, they essentially become a food pantry for younger beings like new seedlings, fungi, and so forth.

Now–what’s so special about the nutrients in salmon? Well, remember that these fish spend years out in the ocean. And the ocean has an entirely different balance of nutrients floating around in it compared to what’s found in fresh water or on land. The salmon are essentially the only way these ocean-borne nutrients can make their way into the forest in any meaningful amount, and they do so on a regular basis each year. The trees near salmon runs fished by bears may be 300% larger than usual, and salmon also provide nearly three quarters of the nitrogen in the forest. That’s a pretty impressive contribution!

This isn’t just about how forests need salmon; it’s a reciprocal relationship. While the salmon’s immediate habitats are aquatic, these streams, rivers, and other waterways are directly affected by what happens on the land around them.

Every waterway has a watershed–an area of land from which precipitation drains into that waterway. These watersheds nest within each other; the watersheds of small streams are nested within the watersheds of the rivers the streams feed into. That water carries things with it, from soil to pollutants. So the health of the land has a direct impact on what is found in the water.

But it goes beyond what’s washed downstream, and into how it’s washed down. In a healthy forest, for example, the soil is able to absorb a significant amount of precipitation that falls throughout the year, keeping it from simply cascading down hillsides to create flooding and landslides. Water is also stored in the various living beings in the forest; again trees are often the champions with their great size, but smaller plants help with water retention quite a bit as well, both through internal storage and preventing evaporation from soil. A forest that is badly damaged, such as through a clearcut or wildfire, won’t hold water as well. This can lead to floods, landslides and other erosion, and increase the impact of summer droughts as the land simply can’t store as much water, or for as long.

All of this affects the salmon directly. If the watershed is no longer holding and releasing snowmelt, rain, and other water in a controlled manner, this can lead to flooding in waterways which can wash away salmon eggs and fry. Increased erosion buries the gravel that salmon lay eggs in with silt, smothering the eggs so they never hatch. When a riparian zone–the land along a waterway–is stripped of vegetation, the water loses crucial shaded areas that keep temperatures cool. Salmon easily overheat when temperatures rise even a few degrees. And drought can dry up smaller streams, stranding and even killing young salmon while preventing adults from reaching their spawning grounds.

While not every single salmon run exclusively travels through forests, many of them do. And many spawning grounds are found in forests, or at least areas with significant tree cover in riparian zones. Salmon must have healthy forests in order to continue to survive, and the loss of these forests is just one of many factors contributing to their severe decline.

Thankfully, I am far from the only person concerned about the safety of our wild Pacific salmon. There are numerous organizations working to protect and restore salmon habitat through dam removal, preservation and restoration of aquatic habitat and surrounding land, regulations on salmon fishing, and educating people about sustainable seafood options (or just not eating seafood at all.) And even habitat restoration efforts that aren’t directly in salmon-inhabited waterways still have a positive impact on the forest ecosystem as a whole.

We know that forests need salmon, and salmon need forests. To protect one is to protect the other, and long may they both thrive.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#long post#salmon#fish#forests#nature#ecology#science#science communication#scicomm#wildlife#bears#Pacific Northwest#PNW#ecosystems#biology#extinction#endangered species#conservation#environment#environmentalism

609 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“THE PMA MASIDLAWIN CLASS OF 2020 STRIKES MANILA”

The PMA MASIDLAWIN CLASS OF 2020 had just concluded their INTERDISCIPLINARY TOUR which is a part of their academic curriculum during their second class year in PMA. The INTERDISCIPLINARY TOUR is an annual activity of the second class and third class cadets, wherein cadets will visit historical and conservation sites to enhance the cadets learning on history and the environment. To LEARN is the primary objective of the tour and somehow to give the cadets time to relax and enjoy while learning.

The cadets visited the Manila Ocean Park which is the only oceanarium in Manila. It is located behind the Rizal Park and the Quirino Grandstand. The park was constructed on 2007 and opened on March 2008. It houses 14,000 sea creatures which are all indigenous in Southeast Asia. It also houses land creatures which are only limited in numbers. It is a famous tourist attraction and the park is visited by tourists and used for educational purposes such as student field trips.

the Philippine Eagle is now an endangered species...

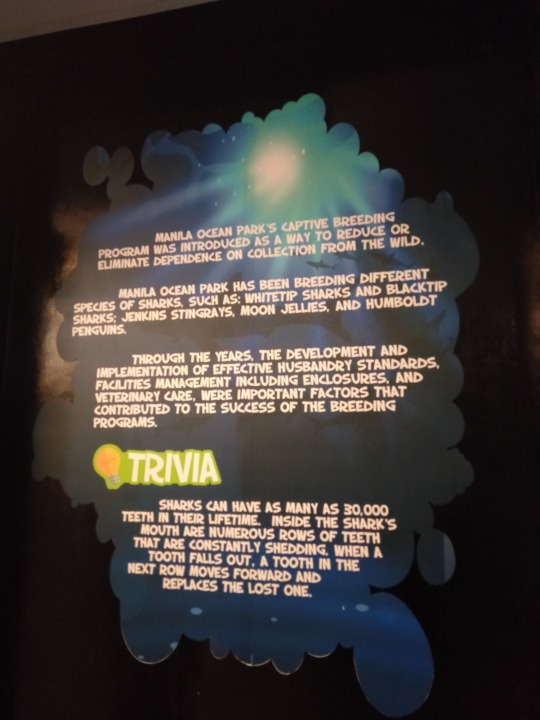

The Manila Ocean Park is not only an attraction but also it’s a conservation for animals. The park also showcases animals that are saved from harm like poachers. The park is home to many animals that are near to extinction. The researchers in the park are keeping these animals saved from extinction. They reproduce these animals through natural and artificial reproduction.

There are many fishes present in the oceanarium such as FRESHWATER organisms like:

1. Giant Moray Eel - are a family of eels whose members are found worldwide. The approximately 200 species in 15 genera are almost exclusively marine, but several species are regularly seen in brackish water, and a few are found in fresh water. 2. Giant Grouper - is the largest bony fish found in coral reefs, and the aquatic emblem of Queensland. 3. Yellowtail Fusilier - is a pelagic marine fish belonging to the family Caesionidae. 4. Bat-fish - is a genus of Indo-Pacific, reef-associated fish belonging to the family Ephippidae. There are currently five known extant species generally accepted to belong to the genus. They are one of the fish taxa commonly known as "batfish". 5. Golden Trevally - is a species of large marine fish classified in the jack and horse mackerel family Carangidae, and the only member of the genus Gnathanodon. 6. Redtoothed triggerfish - is a triggerfish of the tropical Indo-Pacific area, and the sole member of its genus. 7. Unicorn Tang - is a tang from the Indo-Pacific. It occasionally makes its way into the aquarium trade. It grows to a size of 70 cm in length. It is called kala in Hawaiian, and dawa in New Caledonia. 8. Snapper - is a species of snapper native to the western Atlantic Ocean including the Gulf of Mexico, where it inhabits environments associated with reefs. This species is commercially important and is also sought-after as a game fish. 9. Napoleon Wrasse - is a species of wrasse mainly found on coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific region. 10. Spotted Eagle Ray - is a cartilaginous fish of the eagle ray family, Myliobatidae. As traditionally recognized, it is found globally in tropical regions, including the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans.

there are also SALTWATER organisms present in the oceanarium such as:

1. White Tip Sharks - is a large pelagic requiem shark inhabiting tropical and warm temperate seas. Its stocky body is most notable for its long, white-tipped, rounded fins. 2. Black Tip Sharks - is a species of requiem shark, and part of the family Carcharhinidae. 3. Jenkins Stingrays - is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, with a wide distribution in the Indo-Pacific region from South Africa to the Malay Archipelago to northern Australia. 4. Moon Jellies - is a widely studied species of the genus Aurelia. All species in the genus are closely related, and it is difficult to identify Aurelia medusae without genetic sampling; most of what follows applies equally to all species of the genus. 5. Humboldt Penguins - is a South American penguin that breeds in coastal Chile and Peru. Its nearest relatives are the African penguin, the Magellanic penguin and the Galápagos penguin. 6. Clown Fish - are fishes from the subfamily Amphiprioninae in the family Pomacentridae. 7. Spiny Sea horse - also referred to as the thorny seahorse, is a marine fish belonging to the family Syngnathidae, native from the Indo-Pacific area. 8. Sea Lions - are sea mammals characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short, thick hair, and a big chest and belly. 9. Sea Turtles - are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. 10. Pajama Cardinal Fish - is a species of fish belonging to the family Apogonidae. It is a popular aquarium fish.

TRIVIA:

The City of Manila... What a place. the city life the bright lights the noise the pollution. Metro Manila is the central city of the Philippines. It is full of commercial buildings and structures. Its environment is different than the others because it is lacking of trees which makes the city warmer. Trees were cut down for commercial spaces and subdivisions. There is always consequences when you deal with mother nature. Manila is home to some stray animals like dogs, cats, rats, squirrels and foxes. You can found them anywhere walking in the street or hiding in the corner looking for garbage as food.

Since Manila is full of infrastructures the soil is also affected by buildings being build in all areas. Factories in the area can cause pollution to the soil, destroying the ecosystem in cities. These factories also produce chemicals into the air polluting the air that we breathe in. This can cause people to get sick and infected. The noise pollution is very present in the area which makes living here uncomfortable.

In Metro Manila, the climate is hot. Even at night it is very hot. This happens because of lacking of trees in the area. Trees were cut down to create buildings, this will cause the increase in heat because no trees will absorb the heat of the area.

Metro Manila is the central city of the Philippines. This means that this is the center of economic transactions in the country. But did you know that the current situation in Manila can improve our economy and also our lives. Solar power can be a good source of energy in Manila by providing solar panels for electricity production. This will lessen the power consumed by providing solar power to replace it. Buses will be provided to lessen car consuming activities in Metro Manila. It will decrease the production of carbon dioxide from cars. Natural gases can be made by dumps to provide an alternative source of gas to be used in day to day living.

So this trip is very memorable to me. I learned a lot in this trip. This trip makes me realized how grateful that we are alive. We are shown to the beauty of God’s creation. His magnificent grace is very alive in our hearts and eyes. The animals are very fantastic which some of them I only saw for the first time because of this trip. This trip makes us also more responsible for our environment, since it is in our hands the future of our planet. Each of us are responsible to our environment. We must save our planet while we still can. We must protect and conserve our endangered animals before they will go extinct. I also realized that I don’t want to live in the city. I came from a province and I can really compared the life in the city and the province. I learned a lot in this trip. It is an eye opening for me to see the current situation in our environment and our country. As future leaders of the AFP, it is our duty to serve and protect not only the people but also our environment. Anyone can be a savior of our planet. First, we should start it with ourselves. Then everything will come by. GOD BLESS to everyone :)

-LOBATON, 2019

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Diamondback Terrapin

The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) or simply terrapin, is a species of turtle native to the brackish coastal tidal marshes of the eastern and southern United States, and in Bermuda. It has one of the largest ranges of all turtles in North America, stretching as far south as the Florida Keys and as far north as Cape Cod. This turtle can survive in freshwater as well as full-strength ocean water but adults prefer intermediate salinities. Terrapins live quite close to shore, unlike sea turtles, which wander far out to sea; however, a population of terrapins on Bermuda has been determined to be self-established (not introduced by humans)

The name "terrapin" is derived from the Algonquian word torope. The name originally was used by early European settlers in North America to describe these brackish-water turtles that inhabited neither freshwater habitats nor the sea. It retains this primary meaning in American English. In British English, however, other semi-aquatic turtle species, such as the red-eared slider, might be called a terrapin.

The common name refers to the diamond pattern on top of its shell (carapace), but the overall pattern and coloration vary greatly. The shell coloring can vary from brown to grey, and its body color can be grey, brown, yellow, or white. All have a unique pattern of wiggly, black markings or spots on their body and head. The diamondback terrapin has large webbed feet.

Terrapins look much like their freshwater relatives, but are well adapted to the near shore marine environment. They have several adaptations that allow them to survive in varying salinities. They can live in full strength salt water for extended periods of time and their skin is largely impermeable to salt. Terrapins have lachrymal salt glands, not present in their relatives, which are used primarily when the turtle is dehydrated. They can distinguish between drinking water of different salinities. Terrapins also exhibit unusual and sophisticated behavior to obtain fresh water, including drinking the freshwater surface layer that can accumulate on top of salt water during rainfall and raising their heads into the air with mouths open to catch falling rain drops.

Seven subspecies are recognized; the Carolina diamondback terrapin, Texas diamondback terrapin, Ornate diamondback terrapin, Mississippi diamondback terrapin, Mangrove diamondback terrapin, Eastern Florida diamondback terrapin, and the Northern diamondback terrapin. The isolated Bermudan population has not been officially assigned to a subspecies, but based on mtDNA it is closely related to the population from the Carolinas.

Diamondback terrapins live in the very narrow strip of coastal habitats on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States. In most of their range terrapins live in Spartina marshes that are flooded at high tide, but in Florida they also live in mangrove swamps. They have no competition from other turtles, although snapping turtles do occasionally make use of salty marshes. It is unclear why terrapins do not inhabit the upper reaches of rivers within their range, as in captivity they tolerate fresh water. It is possible they are limited by the distribution of their prey. Terrapins tend to live in the same areas for most or all of their lives, and do not make long distance migrations.

Diamondback terrapin diets are not generally well studied, and almost all work on diets has been done in the southeastern part of their range. They eat shrimp, clams, crabs, mussels and other marine invertebrates, especially periwinkle snails. At high densities they may eat enough invertebrates to have ecosystem-level effects, partially because periwinkles can themselves overgraze important marsh plants.

In the 1900s the species was once considered a delicacy to eat and was hunted almost to extinction. The numbers also decreased due to the development of coastal areas and, more recently, wounds from the propellers on motorboats. Another common cause of death is the trapping of the turtles under crabbing and lobster nets. In July 2016, the species was removed from the New Jersey game list and is now listed as non-game with no hunting season. In Connecticut there is no open hunting season for this animal. There is limited protection for terrapins on a state-by-state level throughout its range. There is no national protection except through the Lacey Act, and little international protection. Terrapins are still harvested for food in some states. There is an active casual and professional pet trade in terrapins and it is unknown how many are removed from the wild for this purpose. Some people breed the species in captivity and some color variants are considered especially desirable.

Diamondback terrapins are the only U.S. turtles that inhabit the brackish waters of estuaries, tidal creeks and salt marshes. With a historic range stretching from Massachusetts to Texas, terrapin populations have been severely depleted by land development and other human impacts along the Atlantic coast. Traps used to catch crabs both commercially and privately have commonly caught and drowned many diamondback terrapins, which can result in male-biased populations and local population declines and even extinctions. Terrapin-excluding devices are available to retrofit crab traps; these reduce the number of terrapins captured while having little or no impact on crab capture rates. In some states, these devices are required by law. Terrapins are killed by cars when nesting females cross roads and mortality can be high enough to seriously impact populations. Nests, hatchlings, and sometimes adults are commonly eaten by raccoons, foxes, rats, and many species of birds, especially crows and gulls. Density of these predators are often increased because of their association with humans. Predation rates can be extremely high; predation by raccoons on terrapin nests at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in New York varied from 92-100% each year from 1998–2008.

Maryland named the diamondback terrapin its official state reptile in 1994. The University of Maryland, College Park has used the species as its nickname (the Maryland Terrapins) and mascot (Testudo) since 1933, and the school newspaper has been named The Diamondback since 1921. The athletic teams are often referred to as "Terps" for short. The terrapin has also been a symbol of the Grateful Dead because of their song "Terrapin Station". Many images of the terrapin dancing with a tambourine appear on posters, T-shirts and other places in Grateful Dead memorabilia.

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

tophatandboots replied to your post “voldemar0336 replied to your post “i am not joking about the baltic...”

Was it the baltic that also had a problem with invasive jellyfish?

i do not think so. if i it have, i have not heard of it anyway. the baltic sea have, to my knowledge, just 1 jellyfish the moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita). sometimes they are very many, both like, they are soppused to be in the ecosystem. also in the north sea, which is a the part of the atlantic that borders the baltic sea, there lives lion's mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata). they sometimes appear in border zone of the two seas, but they are not invasive there, as much as just, having become confused and on accident ended up in brackish water lol.

something that HAVE been a massive problem in the baltic is invasive crayfish though. we swedes eat crayfish. and at some point, SOMEONE got the bright idea to plant in a crayfish spacies that is not native to the baltic sea, to get be able to fish up more crayfish!

yes............................................

that was a mistake. big mistake.

the species native to the baltic sea is named European crayfish (Astacus astacus), and the species that have been planted in is signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus), which belong in the american ecosystem.

anyway, in the baltic sea, the signal crayfish spreads a disease which has almost wiped out the entire european crayfish species from the baltic sea, because our crayfish had no immunity against the disease.

and ANYWAY, this keeps being a thing, becuase people illegally plant out the signal crayfish, in the belief that is will survive better, which just weakens the european crayfish, which belong to the baltic sea ecosystem. and as mentioned, the baltic sea ecosystem is very sensitive to changes. and well.

Crayfishing FIshing Politics is a thing in sweden, and like Crayfish Fishing Crimes, haha.

so, that is the invavsive species in the baltic sea i spountansly think off! because it has been a massive problem in swedish waters of baltic sea. i am sure there are more invavsive species over here tho. just, that is the Famous Example in sweden.

@tophatandboots

#tophatandboots#norsesuggestions#norsereply#i am no natural scientis#so here i rely entiraly on like newspaper articles and other info i can google forward#like things that is general knowledge#so disclaimer might have gotten something wrong

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Co-Evolution of the Willow (Genus Salix) and Humankind with Particular Emphasis on Estuarine and Delta Systems- Juniper Publishers

Introduction

The willow (genus Salix) thrived in the floodplain environment since the upper cretaceous period, e.g. fruiting Salix catkins were found in the Pipe Creek Valley, Dakota (Figure 1). The life history of Salicaceae is closely related to riverine habitats. Therefore, characteristic traits have evolved. Efficient seed production is followed by establishment on exposed riverine sediments and fast growth. High bending capacity and breaking resistance make Salix shrubs and trees resilient to river currents and waves [1], erosion and sedimentation processes [2]. Moreover, plant parts resprout vigorously after fragmentation by physical disturbance and flooding [3].

Ancient civilisations developed settlements along major flows. Willows naturally occurring in floodplains were used for dwellings along the Euphrates more than 10.000 years ago and for construction, tool handles, hoes and ploughs during the dynasty of Ur in Mesopotamia [4]. Willows provided flexible twigs and branches for furniture, fences for shelter, and fish traps. Willow baskets for food, supply and for storage may have been among the first articles manufactured by human hunter-gatherer communities [5]. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO [4] highlights willows as “Trees for Society and the Environment” serving humankind since the dawn of history.

Global Distribution

Salix is a globally distributed species rich genus that can be divided into two ecological groups, (i) non-alluvial species of forest, rocks, wetlands with stagnant water and prostrate shrubs of tundra and alpine habitats, and (ii) narrow-leaved alluvial tree and large shrub species adapted to floodplains used for their flexible shoots [6]. The largest tree Salix species belong to the widely distributed and cultivated willows of the floodplain environment (Figure 2). The white willow (Salix alba L.) forms softwood floodplain forests throughout Europe up to North Africa, Asia Minor and western Asia, and is worldwide planted near human habitations and on riverbanks. The Black willow (Salix nigra M.) forms extended forest stands along large rivers in North America, whereas S. humboldtiana W. is the only Salix species native to South American floodplains [7]. Salix phylogeny is complex due to frequent interspecific hybridization. Hybridization accompanied by polyploidy likely played a major role in modern Salix species evolution in genetically variable populations in disturbed floodplains and in cultivation [1].

Estuarine and Delta Systems

In South America, S. humboldtiana settles on non-tidal sandy deposits up to where the lower Parana Delta propagates in the Rio de la Plata estuary. Estuarine islands have been subjected to land use change since decades and today willow-plantations cover extended tidal freshwater wetlands [8]. Tidal freshwater wetlands were occupied by humans since they developed in coastal plain estuaries during the last 6.000 years. Ports were established because these sheltered locations were the most inland point in the estuary that could be reached by ships and where river discharge prevents salt water intrusion, but flat topography allows tides to determine the geomorphology and hydrodynamics [9].

Along the US Atlantic coast, downstream located oligohaline marshes were transferred into tidal freshwater forested wetlands due to colonial land clearance 300-500 years ago shifting sediment into tidal wetlands, resulting in increased accretion. More recently, tidal freshwater forest declines due to tidal inundation and increasing salinity from sea level rise [10], e.g. in the Mississippi Delta where the Black willow forms extended forest stands. Similarly, S. humboldtiana may be substituted by some ten-thousand hectares of tidal forest plantations consisting of hybrid-willows (S. alba and S. babylonica L. (syn. S. matsudana Koidzumi) genotypes exist in the Rio de la Plata Delta. Salix babylonica grows originally in sandy river valley depression in arid-semiarid regions of China with pendulous branches. The weeping willow is one of the most widely used tree in horticultural and environmental application [7] eventually due to adaptation to changing water levels.

North Sea Region

In the North Sea Region, vast tidal freshwater wetlands containing willows still occur along the Scheldt, Belgium, the Weser and the Elbe, Germany, in De Biesbosch and along the Oude Maas in the Netherlands [11]. Most European TFW were utilized by humans for similar reasons as in North America due to the availability of water, nutrient-rich soils for agriculture and the abundance of fish, shellfish, mammals, and plants for food and shelter. However, humans may have also been negatively impacted by flooding and mosquito-borne diseases [9]. Willows extract large quantities of water due to high evapotranspiration rates (phreatophyte-type of vegetation), and from historical references it is reported that willow plantations in malaria affected areas were the most effective for drying up the earth and thus sheltered human settlements [12]. The pulverized bark of Salix alba is even said “its having the properties of the Peruvian bark” and similar effects on “the agues” [13]. The “Marsh-Fever” occurred in brackish coastal and estuarine areas in North-West Europe connected to the occupational history. These areas were exploited by Ertebolle and Swifterbant people since the 5th millennium BC. Subsequent sedentary communities utilized fertile marshes and estuarine forests for pasturage and agriculture. The coastal malaria vector Anopheles atroparvus found hibernation chances in human settlements, stagnant brackish water provided sites for breeding in oxbow lakes and health risks increased in embanked polders with high-days from 1500-1750 AC [14].

Severe storm surges damaged dikes during that time. This lead to dike reinforcement along the Elbe estuary whereas pollard willows were planted along the dike for protection against surge and ice-scour (Figure 3). The willow plantations led to sediment accretion and prepared the foreland for the use as meadows and pastures. In addition, willow rods were harvested, used for fascines and groynes, and since 1800 until 1950 an extended willow culture for basketry, furniture is reported for most of the Haseldorfer Marsch [15], one of Europe`s largest tidal freshwater wetlands. However, after a major flood in 1962 a new constructed dikeline lead to the loss of approximately 75% of the former TFW area in the Haseldorfer Marsch. De Biesbosch consisted of approximately 8,000 ha TFW but lost vast areas due to the construction of a storm surge barrier. However, still more than 1.500 ha TFW exist including bulrush (Bies = Dutch word for bulrush; Bosch = bush) at lower and willow forests and coppices at higher elevations [11]. Bulrush and willows enhance sediment deposition and floodplain landform construction controlling ecosystem changes in space and in time [2]. Thus, creation of vegetated tidal wetlands in suitable locations for ecosystem-based coastal defence is recently proposed as an economic and ecologic supplement to conventional engineering [16].

These findings suggest that the floodplain willow is not only key resource and develops floor for life but evolves valuable and characteristic traits due to human cultivation what leads to the call “Make me a willow cabin at your gate” to implement tidal willow forest plantation and restoration [3].

Acknowledgement

The author likes to thank the colleagues at Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research Yerseke, NL, for fruitful discussion on the topic and Matthias Michalczyk, Friedrich-Wilhelm University Bonn, Department of Geography, for valuable comments that helped to improve the manuscript. We further thank the editors for the invitation to contribute to the journal.

I further wish to thank my colleagues in the Department Wetland Sciences and Engineering at University of Maryland for inviting me as a guest scientist to study the Chesapeake Bay tidal wetlands and the Genus Salix in Maryland and Washington DC.

To know more about Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjaa/index.php

To know more about our website click on Open access Journals publishers: Juniper Publishers

1 note

·

View note

Text

Georgetown Strategy Group: First Annual Letter - 2019

DEAR FRIENDS:

On May 1, 2018 at 6:00 am, we launched the Georgetown Strategy Group with a social media campaign attracting 20,000 people in its first days. Last week, the the Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee introduced me, “the Managing Director of the Georgetown Strategy Group,” as its first witness of the new 116th Congress to speak about U.S. Policy in the Arabian Peninsula (read statement and watch hearing). Every day in between has been heady, exciting, exhausting but always interesting.

OUR MISSION

From the outset, the Georgetown Strategy Group had one mission: to leverage talent, technology, and capital to help solve some of the world’s most complex problems. Working with the private sector, communities, and governments, the Georgetown Strategy Group seeks to promote trade and investment, develop economic opportunity, advance security and stability, and facilitate the delivery of humanitarian assistance in the Middle East and Africa. The leaders of the Georgetown Strategy Group have dedicated their lives to improve the human condition. We have designed and managed programs to deliver essential services; negotiated agreements to facilitate the movement of goods and people; developed businesses and tech ecosystems; and contributed to building more effective institutions throughout the Middle East and Africa during times of war and crisis.

THE RESULTS

In the first 8 months, the firm has demonstrated profitability, growth, and impact. Revenue exceeded projections; strong earnings continue in early 2019. The firm has diversified its client base with 12 customers and prospects for 50% further growth by the end of the first full operating year. Importantly, the firm has no long term liabilities and has sufficient financial sustainability to continue to grow. Aside from a financial bottom line, the firm has assisted non-governmental organizations and for-profit corporations manage critical challenges. The firm is positioned to take advantage of the growing nexus between capital and technology in frontier markets. We have advised FinTech companies intending to launch in Yemen, agricultural firms seeking to open high-end markets; structured big data analytics throughout the Middle East, Asia, and Africa; provided strategic management for leading DC consulting firms; and helped bring pre-commercial research and development of remote sensing, advances in renewable power and water, and operational research and analysis to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS

The Georgetown Strategy Group (GSG) entered into two strategic partnerships in 2018. In June, GSG announced its partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory. MIT’s mission is “to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world,” and through Lincoln Laboratory, has developed novel technologies in support of stabilization and humanitarian assistance. The Georgetown Strategy Group and MIT Lincoln Laboratory seek to disrupt and improve humanitarian and disaster assistance response capabilities to meet the most pressing challenges of this century.

In November, the Georgetown Strategy Group entered into a joint venture with Souktel Inc., a leading provider of custom digital solutions solutions for emerging markets. Through this partnership, the firms will work jointly to expand into new markets across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia — building on Souktel’s decade-long track record of digital solutions delivery, to add new private sector business lines in 2019. With the launch of the new partnership, I have assumed the role of Chief Executive Officer for Souktel, Inc. and will continue to lead GSG.

INTREPID OPPORTUNITIES

While scouting opportunities for the Souktel-Georgetown Strategy Group joint venture, I traveled to Gaza in December. This time not as a diplomat, journalist, or aid worker, but rather as an entrepreneur in search of software developers and rugged water technologies. My first stop: Gaza Sky Geeks. This Mercy Corps incubator operating in Gaza City helps startups build products and offers teams of designers and full stack developers for international clients. I then met with the CEOs of half a dozen firms leading the Gaza tech sector; these firms are doing early stage outsourcing in the region and beyond. Collectively, their firms employ over 150 engineers who work through blackouts, disruptions, and conflict to deliver services to the world. The eager young developers at Gaza Sky Geeks, coupled with the more seasoned tech firm leaders, provided great insight into the emerging talent, passion, creativity, and drive that can flourish, even in one of the most challenging of circumstances.

Software is not the only nascent sign of hope. The collapse of the water aquifer and the resulting necessity of desalination of nearly all the water in Gaza has propelled new thinking in water and treatment technology that could be viable in frontier markets around the globe. MIT is piloting a community based off-grid solar desalination plant for brackish water; this technology is pre-commercial but primed to hit emerging markets in 2019. This technology adapted in Gaza would be effective for the people of Yemen and can readily be employed as an off-grid alternative to refugee communities along the Syrian border or in the horn of Africa. Moreover, Gaza is ripe to test other, newer technologies such as air-to-water systems, greywater re-use in rugged environments, and private community solar and water, obviating the need for large-scale government infrastructure.

THE MEDIA

The firm’s expansion strategy includes building a name brand public platform. In the first 8 months, the firm has been prominently referenced in leading U.S. and international media including the New York Times, National Public Radio, The Hill, The Atlantic, Associated Press, United Press International, and Jerusalem Post coupled with television interviews on Al Jazeera, i24, TRT and other channels. This profile has led to numerous speaking engagements throughout the country and has helped to drive business opportunities in the Middle East and beyond.

POSITIONING FOR THREE TRENDS IN THE NEXT DECADE

The Georgetown Strategy Group sees three macro political-economic trends shaping the Middle East and Africa in the decade ahead

First, the world order as largely built by the U.S. post-World War II, which has served as the greatest force for peace and prosperity in history, is being challenged by emergent world leaders. These WWII institutions, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the UN, and the multilateral finance banks served as global shaping forces for more than 70 years. We are now witnessing the rise of a new great game with China, Russia, Turkey, and Iran vying for power, position, and markets throughout the Middle East, particularly in the Arabian Peninsula as well as in the Horn of Africa.

Second, the decade ahead will be defined by rapid technological changes, (particularly in artificial intelligence and big data analytics), rapid public and private capital flows (including increased financing from non-U.S. sources), the continued mass movement of people across borders and regions as we have seen in Syria, and a shifting of markets and trade routes away from the dollar economy in favor of our rising nation state challengers.

Third, national aspirations, particularly in the Gulf states, will result in unprecedented opportunity and serious inflection points for American business leaders. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are rising regional powers with complementary and, at times, competing geo-political interests. Saudi Arabia has an ambitious economic vision for 2030 that will require a respect for human rights and consistent rule of law if it hopes to actually implement its vision. The United Arab Emirates seeks economic expansion and political influence, as demonstrated specifically by its race to build regional seaports, boost trade partnerships, and create new markets. Rising national aspirations, coupled with rapid technological and financial trends, will likely accelerate the Israel-Sunni bloc re-alignment in way which will be exciting and unexpected in the U.S.

THE YEAR AHEAD

The Georgetown Strategy Group has a bold vision for 2019. Specifically, the firm seeks to aggressively position for market share at the corner of capital and technology. Further, the firm’s agility and speed will allow it to effectively capitalize on the three macro political-economic trends ahead. This vision will begin by expanding into power and water technologies adaptable for complex crises in the first quarter of 2019. This strategic alignment coupled with Souktel’s corporate capabilities will position both firms to drive transformative impact in frontier markets throughout 2019.

CONCLUSION

The future favors the bold. The Georgetown Strategy Group seeks create a legacy that positively shapes and influences the future for generations. 2018 was just the start.

Sincerely,

R. David Harden

***Originally published on Medium by R. David Harden.***

#georgetown strategy group#georgetown#arabian peninsula#116th congress#managing director of the georgetown strategy group#House Foreign Affairs Committee#financial sustainability#nexus#frontier markets#Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory#North Atlantic Treaty Organization#multilateral finance#legacy#Souktel#political-economic trends

0 notes

Text

We are so fortunate! We’ve gotten to visit St Augustine and Florida’s Historic Coast a few times now and each time we love it more and more. On this most recent visit we got to spend a lot more time exploring the nature of the area and we’ve got some awesome ideas for outdoor activities around St Augustine.

Everybody thinks of St Augustine for its history and being the coolest town in America, and rightly so, but there a lot more to it as well. Being a perfect blend of beaches, swamp land and estuaries, outdoor activities around St Augustine will keep you busy as you create an exciting adventure.

St Augustine Beaches

How can you ever talk about visiting Florida without hitting the beach. We’ve learned how to schedule our days with the kids to allow for playing tourist and seeing the sights and also having a good amount of beach time. When you’re in the area, outdoor activities around St Augustine ALWAYS afford for beach time.

Ponte Vedra Beach

North of the city of St Augustine is Ponte Vedra. Yes, it’s the land of beautiful homes and golf courses, but it’s also a wonderfully long strip of beach with just the right waves for playing. We opted for the beach access across from the GTM Reserve, Guana Tolomato Matanzas Research Reserve, as there was a parking area and actual crosswalk to the beach.

The beaches of Ponte Vedra were great for beach combing as well as playing in the sand. The texture was just perfect with enough chunkiness to not make a huge mess in the car but soft enough to feel amazing between your toes. And it’s absolutely beautiful. The waves here are just large enough to be exciting for adults but also small enough that you can feel safe playing in them with older kids. We even attempted to teach our oldest how to boogie board here!

Tip: depending on your travel style or where you’re staying you may have beach toys at your fingertips. Always keep them in your vehicle just in case you need them. And a good beach umbrella is really helpful too.

Ponte Vedra Beaches are ideal in your plan for outdoor activities around St Augustine as the beaches aren’t terribly crowded and there is very little development around the public access points. We cannot wait to go back!

St Augustine Beach

The shape of the Continental Shelf around North Florida make for varying beach types every few miles. Where Ponte Vedra had some great waves and gritty, shelly sand, St Augustine Beach has a much farther tidal break and the wave take longer to roll in. St Augustine Beach is ideal for a sunny day with smaller kids.

We really enjoyed the beach combing on St Augustine Beach. The shells were quite plentiful and there was a great variety. They were all very different from what we found on the Gulf Coast Beaches. The bird watching was also quite different at St Augustine Beach with a lot more plovers and egrets than up north.

Note: there are some great restaurants in the St Augustine Beach area, so plan on grabbing at least one meal there. We had some tasty Caribbean-American fusion at Mango Mangos and loved it. We even bought some of their special key lime seasoning salt. Delicious.

The Estuaries and Reserves

If you’re unfamiliar, river deltas or marshlands near the beach typically create estuarine environments with lots of dense vegetation that thrives in the brackish waters (fresh/salt water mix). This is also a great place to find shorebirds, dolphins and more.

GTM Reserve Education Center

Starting north in the Ponte Vedra area and heading far to the south is the Guana Tolomato Estuarine Research Reserve. When you’re planning outdoor activities around St Augustine be sure to spend some time here.

Our first stop in the GTM Reserve was at the GTM Environmental Education Center. Have you ever walked into a building with no idea what you’ll find and then come face to face with a near life-sized right whale? Yeah, that was us here. Upon entry we were given a scavenger hunt to guide us through the many exhibits as we learned about the estuary, animal migrations, and the problems marine ecosystems face regarding pollution. It was a great place to show the kids up close why we need to care for the earth.

After some awesome learning we headed outside to check if there were manatees in the river at the moment. There weren’t but we did spy all kinds of birds and loved watching the mullet (fish, not hairdos) jumping and slapping the water around us.

Kayaking the GTM Estuary

South of St Augustine in the town of Marineland there is a marina with a great eco-tour company, Ripple Effect Outdoor Adventures. We met our guide, Leaf, who outfitted all four of us for a day of paddling and then set out across the Inner Coastal Waterway and into the estuary. Before we even got into our kayaks we were watching dolphins playing and fishing right in front of us.

Kayaking is a must when it comes to outdoor activities around St Augustine. With such a diverse environment, how can you not want to explore it up close? Our guide was very passionate about sharing the ecosystem and explaining the different issues facing it, from climate change and its effects to the imbalance of species within the waters.

Tip: when you’re kayaking in unfamiliar waters or in a protected area, book an eco-tour with a naturalist guide. You’ll learn so much, you’ll be safer (for you and nature) and you’ll have an unforgettable time.

As we wrapped up our kayaking in the GTM Reserve we got to observe a couple of dolphins fishing. They were getting playful and putting on quite the show. We were all careful to not paddle towards them, but the dolphins swam all around us. Following this, Oliver, our oldest, told us that he wants to be a naturalist someday. I hope that happens. :)

Tip: always be sure to have extra water with you when you’re kayaking. It’s an incredible workout and you’ll sweat more than you think.

Exploring the Inner Coastal Waterway

Yes, the estuaries on the North Florida Coast are all along the Inner Coastal Waterway, but you can actually get onto the Inner Coastal for its own outdoor activities around St Augustine. Check it!

St Augustine Eco Tours

We love doing boat tours. We’ve done them all over the place, from the Everglades to Mexico to up in the mountains of Glacier National Park. When we boarded our boat with St Augustine Eco Tours we weren’t too sure what to expect, but we’d heard that Zach, the operator, was an amazing naturalist who cared deeply and was great with kids. Totally true.

Going on a power boat on the Matanzas River, aka the Inner Coastal Waterway, was way different than kayaking in the estuary. We were able to head out to Salt Run Bay between Anastasia Island and the city of St Augustine, where we watched dolphins playing and juvenile sea turtles popping up all over the place.

Note: this particular area is really unusual when it comes to a habitat as it’s where many sea turtles live and grow from when they first make their journey into the ocean until they’re adults swimming the open sea. It’s a special spot.

Following exploring the more open bay, we headed up the Matanzas river, learning about shore birds and the fort, the Castillo de San Marcos. It was interesting seeing and learning about the fort from the water; it was a totally different experience.

Moving south we were treated to an exceptional moment: we came across a small congress of manatees feeding…while a family of dolphins went crazy catching fish and throwing them into the air just beyond. It was amazing! The kids loved every minute of it. Our naturalist, Zach, also pulled out an underwater microphone so we could listen to the dolphins. Seriously awesome eco-tour.

If you look closely, you can see two manatees kissing at the surface.

One of the highlights for the kids was riffling through the seaweed that had been swept into the Matanzas River. It’s called sargassum and it drifted in from the middle of the Atlantic Ocean on a crazy, unusual current. Each chunk of this seaweed was full of creatures, from shrimp and crabs, to fish and nudibranchs (sea slugs). So cool!

Tip: if you’d like to really learn about the marine ecosystem of the North Florida Coast or want a trip geared up to make a difference, talk to St Augustine Ecotours about how to spend some extra time with them, and maybe even do some volun-tourism in the area.

Fort Matanzas

We fell in love with Fort Matanzas National Monument on our first trip to Florida’s Historic Coast. Planning an adventure to the Fort is one of our musts for outdoor activities around St Augustine. Located on the western side of the Matanzas River, the National Parks Service does a foot ferry across to its little island at the start of the estuary. Opportunities for wildlife viewing include manatees, pelicans, all kinds of shorebirds, and of course, dolphins. The Fort is really neat and the history you get with the tour is fascinating.

Note: 2016’s Hurricane Matthew destroyed the ferry dock at Fort Matanzas National Monument, so before adding this stop to your North Florida itinerary, check to confirm if the boat service is operational again. As of April 2017 boat service is still down.

Strolling St Augustine

I know, we’re so water-centric in our family. You can always ensure you’re doing outdoor activities around St Augustine by planning to stroll the city too. We’ve explored so much of the area that I feel like we’re experts… but there’s still a ton for us to see.

Key sites to visit on foot in the main downtown area are the Castillo de San Marcos, St George Street (really cool shops and dining) Huguenot Cemetary, Aviles Street (the oldest street in Florida), and of course, the Sea Wall. There are several types of tours you can do in St Augustine. We’ve done the Old Town Trolley Tour, which is a hop on, hop off tour all through town, and the Ghost Tour of St Augustine…

Old Town Trolley Tour

This was such a great activity with the kids. We started at the Old Town Trolley Tours depot by the Old Jail. Beginning with a completely in-character tour of the jailhouse, including solitary confinement and gallows, was a great way to set the tone for the day. It was fun, historical and hilarious to do with the kids. They both braved the creepy old place.

Continuing on, we hopped on board and headed for the old City Gates. A visit to Castillo de San Marcos National Monument and a walk with Hyppo popsicles down St George St and we were ready to hop back on. We caught the Old Town Trolley Tour right by Flagler College and heard all about the rest of the town. We ended at the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park where Oliver begged us not to drink the water. His argument: “But I love you the way you are.” He’s a keeper.

Ghost Tours of St Augustine

Okay, we split up for this. One dad stayed at our vacation rental and put the kids to bed while the other went on the Ghost Tour of St Augustine. The ghostly tour starts in the old downtown area and winds through the city streets in the dark, led by a costumed guide with a lantern. After hearing the history of the town, the stories of Flagler College and swinging by the cemeteries, you’re pretty much piqued to spot some sort of ghost. Check out the interesting “energy” caught on film.

Tip: whether or not you believe in ghosts and spirits and such, this is a cool tour. Seeing the old town at night is awesome and the night air is a bonus to planning your outdoor activities around St Augustine.

So, now that we’ve visited our favorite Florida city a few times, we’re just about ready to pick up and move here. Outdoor activities around St Augustine are plentiful, the history is abundant, and the charm and fun never cease.

Have you been to St Augustine or anywhere else along Florida’s Historic Coast? What are your favorite haunts or stops? We’re ready to go back to explore more at a moment’s notice, so tell us where to go next!

Outdoor activities around St Augustine: nature on Florida’s historic coast We are so fortunate! We’ve gotten to visit St Augustine and Florida’s Historic Coast a few times now and each time we love it more and more.

0 notes